Dictionary Maker Fights Back as Reference Works Go Electronic

- Share via

BREWSTER, N.Y. — They bore through magazines and pore over cookbooks to find the latest and tastiest phrases. Cheese sandwiches in hand, they argue the finer points of definitions. In this home, it is forbidden to enter the bathroom without taking something to read and mark.

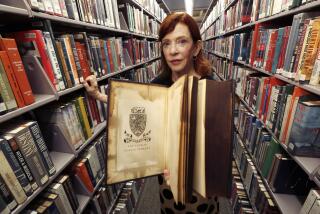

Robert and Cynthia Barnhart and their five children--lexicographers all--toil much as Robert’s father, Clarence L. Barnhart, did: filling, filing and rifling through drawers and drawers of index cards that trace the evolution of American English.

Their Thorndike-Barnhart school dictionaries have long been classroom staples. There are also Barnharts’ New English, etymological, abbreviations and American Heritage Science dictionaries.

But now the family’s biggest source of income--the companion dictionary to the World Book Encyclopedia--is threatened by the growing popularity of electronic reference works over printed ones.

In what they call a fight to preserve their way of life, the Barnharts are suing World Book, seeking royalties for an estimated 200,000 electronic copies of their dictionary.

The case that began in their kitchen in rural Brewster, 70 miles north of New York City, stretches to include IBM Corp., which distributes the CD-ROM dictionary, and billionaire Warren Buffet, whose conglomerate is overseeing a $5-million push to get World Book into the computer age and cut costs along the way.

“It gets to be quite exciting sometimes because the line between survival and extinction is quite thin,” said Robert, who at 63 is a word-loving archetype--puffing a pipe, wearing a cardigan.

“We experience what the dinosaurs did: If the wave of cultural frigidity keeps on, I suppose that some day the Ice Age will come, but we’re fighting against it.”

Meanwhile, the family works much as it has for the last 30 years.

All seven Barnharts--plus in-laws, friends and employees--divide up the immense task of reading what Americans read to see how language imitates life: Rolling Stone to keep up with the younger generation, Foreign Policy for bureaucratic babble, The New Yorker for literary quirks, Scientific American for technical terms, the Journal of Commerce for business innovations, and stacks of books.

“English is a remarkably adaptive language which lends itself to creative uses,” said Cynthia, 62, petting one of their eight terriers. “We don’t judge the new words. If you start cutting it off, then it doesn’t grow.”

*

With their only computer reserved for bookkeeping and office mail, the Barnharts chart the language’s growth by putting new words and the quotations in which they appear onto index cards.

John, 37, a figurative painter who cultivates a Mick Jagger look, makes a preliminary entry list at his tiny Soho apartment. He then travels to Brewster to check the list against the family’s floor-to-ceiling files--5 million index cards that take up 2,400 cubic feet of the basement.

Becca, 26, is the only one not involved in the advanced stages of the dictionary. She files contributions of new words from Washington, where she runs a boutique.

David, 34, a mellow Manhattan cellist, checks the words against “the competition”--other dictionaries.

Then Becca’s twin, Katy, the anointed successor to her father, begins the process of defining.

Michael, 41, who teaches philosophy at the City University of New York, reviews the final definitions and makes what his mother calls “annoyingly clever improvements.”

Once all this is done, “then you hope that the Big Cheese--Dad--will take your definition,” Katy said, her eyes disappearing as she smiles--a family trait.

Lexicography draws the immediate family close, but not the extended family. Relations are “cordial, but distant” with Robert’s younger brother, David, who writes a quarterly newsletter on new words from nearby Cold Spring. There are disagreements over how their late father, Clarence, managed his legacy and the business he started with psychologist Edward Lee Thorndike, with whom he began writing dictionaries in 1928.

The Barnharts focus, however, on surviving in a field dominated by a few publishing houses--all of them using computers.

“At Random House, we have moved along with the rest of the world and everyone sits at a computer,” said Sol Steinmetz, that publisher’s editorial director and a Barnhart employee for 28 years.

“They work in the old traditions of lexicography . . . which is charming in a way, but it’s not as much fun as breezing through the database.”

But the Barnharts say machines don’t make for better dictionaries. Databases catch new words but miss common ones that change meanings over time.

Katy is determined to update the family’s technology, but stressed that “a computer can never function as broadly as a brain can.”

That’s why William Safire, who writes the “On Language” column for The New York Times’ Sunday Magazine, often relies on “Barnhart power” to find the origins of words and phrases, according to Jeff McQuain, Safire’s research associate for the last 14 years.

“They are the ones tracking the growth of the language and suggesting what words will be coming into the language in the future,” McQuain said.

*

Ken Kister, a reference analyst in Tampa, Fla., said the Barnharts’ World Book companion dictionary is the best he has seen. The two-volume dictionary, first published in 1963 and updated each year, has “taken the significant living language and put it between four covers,” he says.

Breathing life into the definitions are quotations dating as far back as the 1600s, culled from the monstrous files lurking underneath the house.

Cynthia Barnhart--who manages the fax-less office using a 1925 Crescent locomotive phone that whistles, chugs and clangs--knows how close the family business is to going under.

Readers have worked for free since the dispute with World Book began. Only sporadically can she find the money to pay the milkman.

“We’re out there on a limb and I guess it’s getting sawed off at the trunk,” says Cynthia.

Lawyers for the Chicago-based World Book did not return phone calls about the lawsuit, filed in May in federal court in New York City. IBM, which began distributing the disputed CD-ROMs this year, also declined to comment.

The Barnharts say World Book claims the electronic version of the dictionary is simply derived from the printed work and that the family has no right to extra compensation for it. The contract does not cover electronic rights, but does stipulate that the Barnharts be given the chance to produce so-called derivative works and negotiate a fee.

World Book, like Encyclopedia Britannica, is struggling in the electronic age. Figures released by World Book’s parent company, Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway in Omaha, Neb., show annual sales have dropped 60% since 1989, from more than $300 million then to $119 million last year.

Encyclopedia publishers are being pushed out of the market by Microsoft’s electronic Encarta, which has better search capabilities and sells for less than one-fifth the cost of a printed encyclopedia, says Kister, the analyst.

World Book doesn’t sell the dictionary separately from its encyclopedia--even though printed dictionaries still sell well because they are easier to use than electronic ones.

“That’s a classic example of where a book is best,” said Gordon Macomber, president of MacMillan Reference USA.

And to its devotees, the Barnharts’ book is best of all.

Katy recalls telling someone she met at a party that she writes dictionaries, and the woman was stunned. “She said she thought only the Thorndikes and the Barnharts wrote dictionaries.

“And I said, ‘I am a Barnhart,’ ” Katy recalled.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.